Canine Vestibular Disease: A Common Senior Dog Malady by Dr. Julie Buzby, DVM

Dr. Julie Buzby, DVM, a member of Grey Muzzle's Advisory Board, is a practicing integrative veterinarian and the developer of ToeGrips®, devices that improve mobility in dogs by providing them with better traction. She has published numerous articles on canine health and wellness, and has a new blog, The Buzby Bark.

I was a newly minted veterinarian when I walked into the exam room and found Foxy, a 13-year-old Blue Heeler, scheduled as a euthanasia appointment. The poor dog couldn’t stand up because she kept falling to one side. She had a distinct tilt to her head, and her eyes were scrolling back and forth in their sockets like a typewriter doing sprints. The symptoms had come on suddenly and the heartsick owners had no explanation. Foxy had been fine the day before. The woman held her dog close, her eyes brimming with tears. Me? I could hardly contain my glee. I would remember that appointment for the rest of my life.

Gently, I extracted Foxy from her owner’s embrace so I could perform a physical exam. (It’s amazing how much information can be gleaned from a thorough exam.) The somber family gathered around, dreading my imminent verdict. They fully expected me to utter: “It’s time, there’s nothing more to be done.”

Instead, after a careful neurologic exam, I proclaimed, “I have wonderful news for you! Odds are excellent that Foxy will recover from this with little to no long term effect and continue to live a normal life.”

The diagnosis? My patient was suffering from idiopathic vestibular disease, which is also known as old dog vestibular disease or canine geriatric vestibular disease, so named because it usually strikes dogs in their golden years.

What does “idiopathic” mean? It means the origin of disease is unknown. Veterinarians joke that idiopathic means, “the doctor is an idiot and can’t identify a cause.”

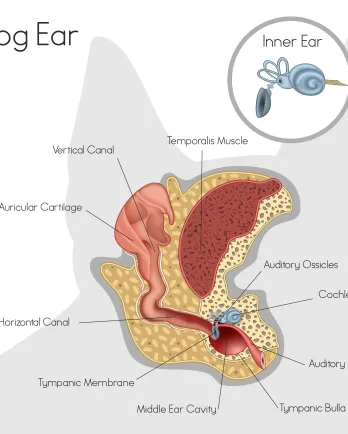

“Vestibular” refers to the vestibular apparatus, located in the inner ear, which perceives the body’s orientation with respect to the earth’s gravitational field. This information is then communicated to the brain, eyes, and body, to maintain appropriate posture and balance.

Symptoms of vestibular disease are similar to vertigo in people. After experiencing a bout of vertigo last year, I’ve developed new sympathy for these dogs. Towards the end of a busy, normal day, I began to feel so dizzy that I couldn’t safely stand up. Within minutes I was vomiting. I crawled to my bed, where just turning my head on the pillow made me sick.

In dogs, classic symptoms of vestibular disease include: loss of balance/ ataxia (the drunken sailor gait), abnormal posture, head tilt, and nystagmus—the medical term for the rapid, uncontrolled eye movement that is the hallmark of vestibular disease.

There is no specific “cure.” We treat these dogs with supportive care on an inpatient or outpatient basis, with lots of TLC, and sometimes acupuncture. Foxy was hospitalized for IV fluids and prescribed a medication to treat motion sickness/ nausea, called Meclizine.

As part of her workup, we ran a complete blood panel, including a thyroid profile, because there appears to be a link between vestibular disease and hypothyroidism in some dogs.

While there are other causes for these symptoms, such as infection (including tickborne disease), cancer, middle/inner ear disease, trauma, and toxins, here’s what is classic in this specific diagnosis:

Symptoms are acute nonprogressive, meaning they come on suddenly and don’t significantly worsen. In fact, they usually improve in the first 72 hours. Full recovery can take 1-4 weeks, but a head tilt may remain permanently, as modeled by celebrity senior dog, Marnie.

A thorough physical and neurologic exam is the most effective place to start sorting out the diagnosis. Idiopathic vestibular disease affects the peripheral vestibular system (inner ear) as opposed to the central system (brain stem). With peripheral disease, we do not see mental dullness/ stupor, or generalized weakness. The dog’s strength is maintained even though his equilibrium is out of whack.

I generally feel comfortable making a presumptive diagnosis in the exam room without advanced diagnostic testing. I do, however, inform owners that there are other possibilities that can present in this way. I cannot be 100% sure of the “old dog vestibular disease” diagnosis without ruling out other conditions through a high-powered work up (which includes a CT scan or MRI), but I think it’s reasonable to begin supportive care and monitor the patient with this classic presentation. If the dog improves in a few days, and is back to normal in days to weeks, the presumptive diagnosis was probably correct.

I still vividly recall Foxy’s appointment because it was the high point of my first year as a veterinarian. Please don’t get me wrong, I was grieved to see the owners and the dog endure some rough days. It took time for her physical condition to match her good prognosis. But a few days after her initial examination, Foxy walked out of our hospital, tail wagging. A slight residual head tilt was all that remained as a reminder of her vet visit. I hugged the owner who was again crying, this time happy tears. In my mind, I had witnessed a dog resurrected from the dead.

The information presented by The Grey Muzzle Organization is for informational purposes only. Readers are urged to consult with a licensed veterinarian for issues relating to their own pet's health or well-being or prior to implementing any treatment.